The history of unified time, from the view point of English history, is an interesting story and includes the story of a self taught Yorkshire carpenter, the history of maritime disasters, the Royal Greenwich Observatory in London and the mess that was the Victorian railway time table.

First, a little history and science. Imagine a grid overlaid upon the Earth, a series of lines running left, right / east west, another set running up, down / north south. The east, west parallel lines are used to identify latitude, those running north south, pole to pole, are those measuring longitude.

Since the first days that Man boarded a boat and sailed from here to there, successfully identifying ones location, using latitude and longitude, ones x-y coordinates on the planets surface, has been problematic. Latitude, for a long time had been understood and many marine devices were devised to chart and record ones latitude. Using the angle of the Sun at its highest point, locally, with the aid of some simple mathematics, could identify ones latitude. At night, a similar exercise using appropriate star charts would provide the same information.

Since the first days that Man boarded a boat and sailed from here to there, successfully identifying ones location, using latitude and longitude, ones x-y coordinates on the planets surface, has been problematic. Latitude, for a long time had been understood and many marine devices were devised to chart and record ones latitude. Using the angle of the Sun at its highest point, locally, with the aid of some simple mathematics, could identify ones latitude. At night, a similar exercise using appropriate star charts would provide the same information.

Determining ones longitude was, essentially, a best guess, known as dead reckoning, based on the last know position or information and extrapolating the next position. However, there was too much unknown information, such as the current of tides, wind speed and direction, to make this reliable. As larger and faster sailing ships would go further the problem of longitude exacerbated the lack of knowledge. Many ships were lost simply by not knowing exactly where they were.

Since the Earth rotates at a steady rate of 360° per day, or 15° per hour there is a direct relationship between time and longitude. If the navigator knew the time at a fixed reference point when some event occurred at the ship’s location, the difference between the reference time and the apparent local time would give the ship’s position relative to the fixed location. Finding apparent local time is relatively easy. The problem, ultimately, was how to determine the time at a distant reference point while on a ship.

There were of course a number of high profile solutions, based on a variety of lunar and, or solar interpretations. Some of the most illustrious names in Science history, including Galileo Galilei and Edmund Halley pitted their wits against the problem. The solutions were ingenious. And flawed. None of the solutions were able to cope with the inherent problems of wind speed and direction, the unknown interactions of the currents and the rocking and rolling movements of the ships themselves and were, often, no more accurate then than the astrolabes they were seeking to replace.

In Spain, during the latter part of the 1500’s, two bounties were offered to successfully devise a marine solution for fixing a longitudinal point. The Netherlands, who, like the Spanish were traversing the globe in ever larger ships, offered 10,000 Florins in the hope of eliciting a solution. The bounties were unclaimed. A century later, Robert Hooke, claimed £1000 in England. He was not paid.

England was also a major power on the water, rivalling those trade routes of the Spanish and the Dutch and building a Navy which would, in future years, secure those trade routes. However, the English were not immune to the same navigational issues as the other maritime powers. Longitude was a problem for all.

In late 1707 the Royal Navy lost four warships, countless bounty and more than 1500 lives. It became known as the 1707 Scilly disaster. It is still one of the worst maritime disasters in the history of the Royal Navy. In short, a fleet of 21 ships left Gibraltar, aiming to return to the southern English port of Portsmouth.

As the fleet sailed out on the Atlantic, passing the Bay of Biscay on their way to England, the weather worsened and storms gradually pushed the ships off their planned course. Finally, on the night of 22 October 1707 the fleet entered the mouth of the English Channel, believing that they were on the last leg of their journey. The fleet was thought to be sailing safely west of Ushant, an island outpost off the coast of Brittany. However, because of a combination of the bad weather and the mariners’ inability to accurately calculate their longitude, the fleet was off course and closing in on the Isles of Scilly instead. Before their mistake could be corrected, the fleet struck rocks and four ships were lost. This was not the only time English ships were lost.

In July 1714, the English Parliament issued the Longitude Act. Within this act three rewards were offered based on differing levels of accuracy and recommended by Sir Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley to the parliamentary committee.

- £10,000 (equivalent to £1.3 million) for a method that could determine longitude within 1 degree (equivalent to 60 nautical miles at the equator).

- £15,000 (equivalent to £1.96 million ) for a method that could determine longitude within 40 minutes

- £20,000 (equivalent to £2.61 million ) for a method that could determine longitude within 30 minutes

John Harrison was neither a sailor not an astronomer. He was a carpenter with a healthy interest in clockwork. As Harrison entered his second decade Harrison had completed a number of wooden clockwork longcase clocks, sometimes known as Grandfather clocks. Most of these early clocks still survive. In his earlier work on sea clocks, Harrison was continually assisted, both financially and in many other ways, by George Graham, the watchmaker and instrument maker. Harrison was introduced to Graham by the Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley, who championed Harrison and his work.

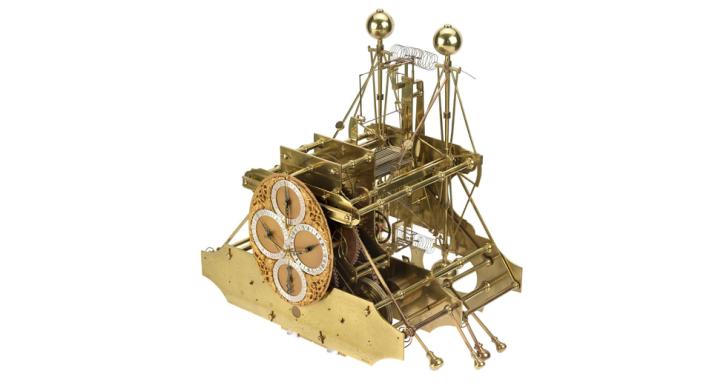

In 1730 Harrisons first Sea Clock, the H1, was designed to be submitted to the Longitude Board. It was the first submission worthy of a sea trial, which was undertaken in 1736. The trial was a success, with the ships Master noting that his own calculations had placed the ship sixty miles east of its true landfall which had been correctly predicted by Harrison using H1.

This was not the transatlantic voyage demanded by the Board of Longitude, but the Board was impressed enough to grant Harrison £500 for further development. Harrison moved on to develop the H2, a more compact and rugged version.

In 1741, after three years of building and two of on-land testing, H2 was ready, but by then Britain was at war with Spain in the War of Austrian Succession and the mechanism was deemed too important to risk falling into Spanish hands. However, Harrison suddenly abandoned all work on this second machine when he discovered a serious design flaw in the concept of the bar balances. He had not recognized that the period of oscillation of the bar balances could be affected by the yawing action of the ship. It was this that led him to adopt circular balances in the Third Sea Clock, the H3. The Board granted him another £500, and while waiting for the war to end, he proceeded to work on H3.

Harrison spent seventeen years working on this third ‘sea clock’, but despite every effort it did not perform exactly as he would have wished. The problem was that, because Harrison did not fully understand the physics behind the springs used to control the balance wheels, the timing of the wheels was not isochronous, a characteristic that affected its accuracy. The engineering world was not to fully understand the properties of springs for such applications for another two centuries. Despite this, it had proved a very valuable experiment as much was learnt from its construction. Certainly in this machine Harrison left the world two enduring legacies: the bimetallic strip and the caged roller bearing. It was now 1758.

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison moved to London in late 1758 where he found that some of the watches made by George Graham’s successor, Thomas Mudge, kept time just as accurately as his sea clocks, H1 and H3. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new “Huntsman” or “Crucible” steel produced by Benjamin Huntsman sometime in the early 1740s which enabled harder pinions but more importantly, a tougher and more highly polished cylinder escapement to be produced.

Harrison then realized that a watch could be made accurately enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper. He proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

By the early 1750’s Harrison had already designed a precision watch for his own personal use, which was made for him by the watchmaker John Jefferys around 1752, or 1753. This watch incorporated a novel frictional rest escapement and was not only the first to have a compensation for temperature variations but also contained the first miniature ‘going fusee’ of Harrison’s design which enabled the watch to continue running whilst being wound. These features led to the very successful performance of the Jefferys watch, which Harrison incorporated into the design of two new timekeepers which he proposed to build.

These were in the form of a large watch and another of a smaller size but of similar pattern. However, only the larger No. 1 watch appears ever to have been finished. This became known as the Harrison Version 4, or H4. It is engraved with Harrison’s signature, marked Number 1 and dated AD 1759.

This first watch took six years to construct, after which the Board of Longitude determined to have is tested on a sea trial, leaving Portsmouth on 18 November 1761, heading to Kinsgton, Jamaica.

When the H4 reached its destination, the watch was found to be 5 seconds slow compared to the known longitude of Kingston, corresponding to an error in longitude of 1.25 minutes, or approximately one nautical mile.

When the H4 returned to England on the 26th of March 1762 to report the successful outcome of the experiment Harrison senior thereupon waited for the £20,000 prize. However, the Board were persuaded that the accuracy could have been just luck and demanded another trial. The board were also not convinced that a timekeeper which took six years to construct met the test of practicality required by the Longitude Act. A second sea trial, with another trip to Barbados was slightly eased as Parliament offered offered £5,000 for the design. Harrison eventually acquiesced.

Enter the contentious character of The Rev Dr Nevil Maskelyne.

In 1760 the Royal Society appointed Maskelyne as an astronomer on one of their expeditions to observe the 1761 transit of Venus. He and Robert Waddington were sent to the island of St. Helena. This was an important observation since accurate measurements would allow the accurate calculation of Earth’s distance from the Sun, which would in turn allow the actual rather than the relative scale of the solar system to be calculated. This would allow, it was argued, the production of more accurate astronomical tables, in particular those predicting the motion of the Moon.[6]

Bad weather prevented observation of the transit, but Maskelyne used his journey to trial a method of determining longitude using the position of the moon, which became known as the lunar distance method.

He returned to England, resuming his position as curate at Chipping Barnet in 1761 and began work on a book, publishing the lunar-distance method of longitude calculation and providing tables to facilitate its use in 1763 in The British Mariner’s Guide, which included the suggestion that to facilitate the finding of longitude at sea, lunar distances should be calculated beforehand for each year and published in a form accessible to navigators.

In 1763 the Board of Longitude sent Maskelyne to Barbados in order to carry out an official trial of three contenders for a Longitude reward. He was to carry out observations on board ship and to calculate the longitude of the capital, Bridgetown by observation of Jupiter’s satellites.

The three methods on trial were Harrison’s H4, Tobias Mayer’s lunar tables and a marine chair made by Christopher Irwin, intended to help observations of Jupiter’s satellites on board ship. Both Harrison’s watch and lunar-distance observations based on Mayer’s lunar tables produced results within the terms of the Longitude Act. Harrison’s watch had produced Bridgetown’s longitude with an error of less than ten miles, while the lunar-distance observations were accurate to within 30 nautical miles.

It is at this point the controversy around Maskelyne is suggested. The second sea trial was concluded in late 1764 with the results presented to the Board of Longitude in early February 1765. In late February 1765 Maskelyne was appointed Astronomer Royal and as such was ex officio a Commissioner of Longitude.

The Commissioners understood that the timekeeping and astronomical methods of finding longitude were complementary. The lunar-distance method could more quickly be rolled out, with Maskelyne’s proposal that tables like those in his The British Mariner’s Guide be published for each year. This proposal led to the establishment of The Nautical Almanac, the production of which, as Astronomer Royal, Maskelyne oversaw. The Harrison family accused Maskelyne of bias, a charge taken up in a number of books recently published on the history of Maritime Chronometers, most notably by Dava Sobel in her book Longitude.

Maskelyne himself did not make a specific proposal to resolve the Longitude problem, however, his belief in the divine ordering of planets surely could not make the The Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne totally impartial.

Maskelyne returned a report of the watch that was negative, claiming that its “going rate” (the amount of time it gained or lost per day) was due to inaccuracies cancelling themselves out, and refused to allow it to be factored out when measuring longitude. Consequently, the H4 failed the needs of the Board despite the fact that it had succeeded in two previous trials.

Harrison began working on his second ‘Sea watch’ the H5 while testing was conducted on the H4. After three years he had had enough; Harrison enlisted the aid of King George III. He obtained an audience with the King.

King George tested the H5 and after ten weeks of daily observations between May and July in 1772, found it to be accurate to within one third of one second per day.

Finally in 1773, when he was 80 years old, Harrison received a monetary award in the amount of £8,750 from Parliament for his achievements. Alas he was not presented with the official award. Parliament did not award the Longitude Prize to anybody. Harrison died in 1776.

The Royal Observatory in Greenwich, where Maskelyne was the Astronomer Royal, was also instrumental in another interesting and important milestone in quantifying time. In 1833 the Royal Observatory installed a time ball to the roof of the Octogon Room, itself a part of Flamsteed House. In simple terms a time ball is a large, usually wooden ball, which is dropped a measurable distance, usually several metres, down a large pole.

The first time ball was erected in Portsmouth, by its inventor, Royal Navy Captain Robert Wauchope, in 1829. It was originally intended to be a method by which a defined time, 1300 hours in the UK, could be indicated to mariners, by which they could set their marine chronometers. The idea was offered to both the American and French Ambassadors to England, with the first American time ball being erected in Washington in 1845.

But it was not just mariners who benefited from the idea of unified time. The early 1800’s saw an explosion of private railway systems in England and around Europe. These lines were built by busy and enthusiastic Victorian entrepreneurs, who had a vision of steam driven locomotion connecting not just the major towns and cities, but the more out laying areas, giving rise to the mobility of people not just for work, but leisure as well. It was the train that, at least in Britain, allowed the working classes to to take day trips to the coast.

However, the problem soon arose with a mis-match of times tables. Noon in one place was not always noon in another place. Where there was a single line or a single operator, this may not have been a problem, but as lines started to interconnect and the idea of a rail network became less nebulous there was a real need to unify, if not time, then at least timetables.

Until the latter part of the 18th century, time was normally determined in each town by a local sundial. Solar time was calculated with reference to the relative position of the sun. This provided only an approximation of time due to variations in orbits and had become unsuitable for day-to-day purposes. It was replaced by local mean time, which eliminated the variation due to seasonal differences and anomalies. It also took account of the longitude of a location and enabled a precise time to be applied.

Such new-found precision did not overcome a different problem: the differences between the local times of neighbouring towns. In Britain, local time differed by up to 20 minutes from that of London. For example, Oxford Time was 5 minutes behind Greenwich Time, Leeds Time 6 minutes behind, Carnforth 11 minutes behind, and Barrow almost 13 minutes behind.

In India and North America, these differences could be 60 minutes or more. Almanacs containing tables were published and instructions attached to sundials to enable the differences between local times to be calculated

As such, in 1840, Railway time was introduced as the the standardised time arrangement first applied by the Great Western Railway. It is the first recorded occasion when different local times were synchronised and a single standard time applied. Railway time was progressively taken up by all railway companies in Great Britain over the following two to three years. The timetables by which trains were organised and the time station clocks displayed were brought in line with the local time for London or “London Time”, the time set at Greenwich by the Royal Observatory, which was already widely known as Greenwich Mean Time or GMT.

The electric telegraph, which had been developed in the early part of the 19th century, was refined by William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone and was installed on a short section of the Great Western Railway in 1839.

By 1852 a telegraph link had been constructed between a new electro-magnetic clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich and initially Lewisham and shortly after this London Bridge stations. It also connected via the Central Telegraph Station of the Electric Time Company in the City of London, which enabled the transmission of a time signal along the railway telegraphic network to other stations.

By 1855 time signals from Greenwich could be sent through wires alongside the railway lines across all of Britain’s rail network. This technology was also used in India to synchronise railway time.

Over the next fifty or so years, almost all countries adopted Greenwich Mean Time as well as the idea or rail time standardisation. By 1916, Germany, Italy, America, The Netherlands, Sweden, India and Korea, had all adopted Greenwich Mean Time at the same time as they standardised their own rail time. The notable exceptions, at least in Europe were France, who created Paris Mean Time in 1891 and Ireland, who had Dublin Mean Time.

The French attacked the problem with traditional Gaelic zeal and required clocks inside railway stations and train schedules to be set five minutes late to allow travellers to arrive late without missing their trains, even while clocks on the external walls of railway stations displayed Paris Mean Time. A very civilised approach if a little chaotic. In 1911, France adopted Paris Mean Time delayed 9 minutes 21 seconds, Greenwich Mean Time without mentioning Greenwich. At the same time, slow railway station clocks were eliminated.

In Ireland, Dublin mean time was set 25 minutes behind London time, although it came into line with international standard time in October 1916 when summer time ended and most railway clocks were adjusted by 35 minutes rather than one hour.

It took more than 200 years to finally arrive at a Standardised time which could be correlated across a country, across a continent and even across continents. From the 1714 Longitude Act which inspired Harrisons work, the central role of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, the 1884 International Meridian Conference, through development of the rail networks around the world and the seemingly independent developments in telegraph technology, we arrived, in 1928 at Universal Time, the new global name for Greenwich Mean Time.